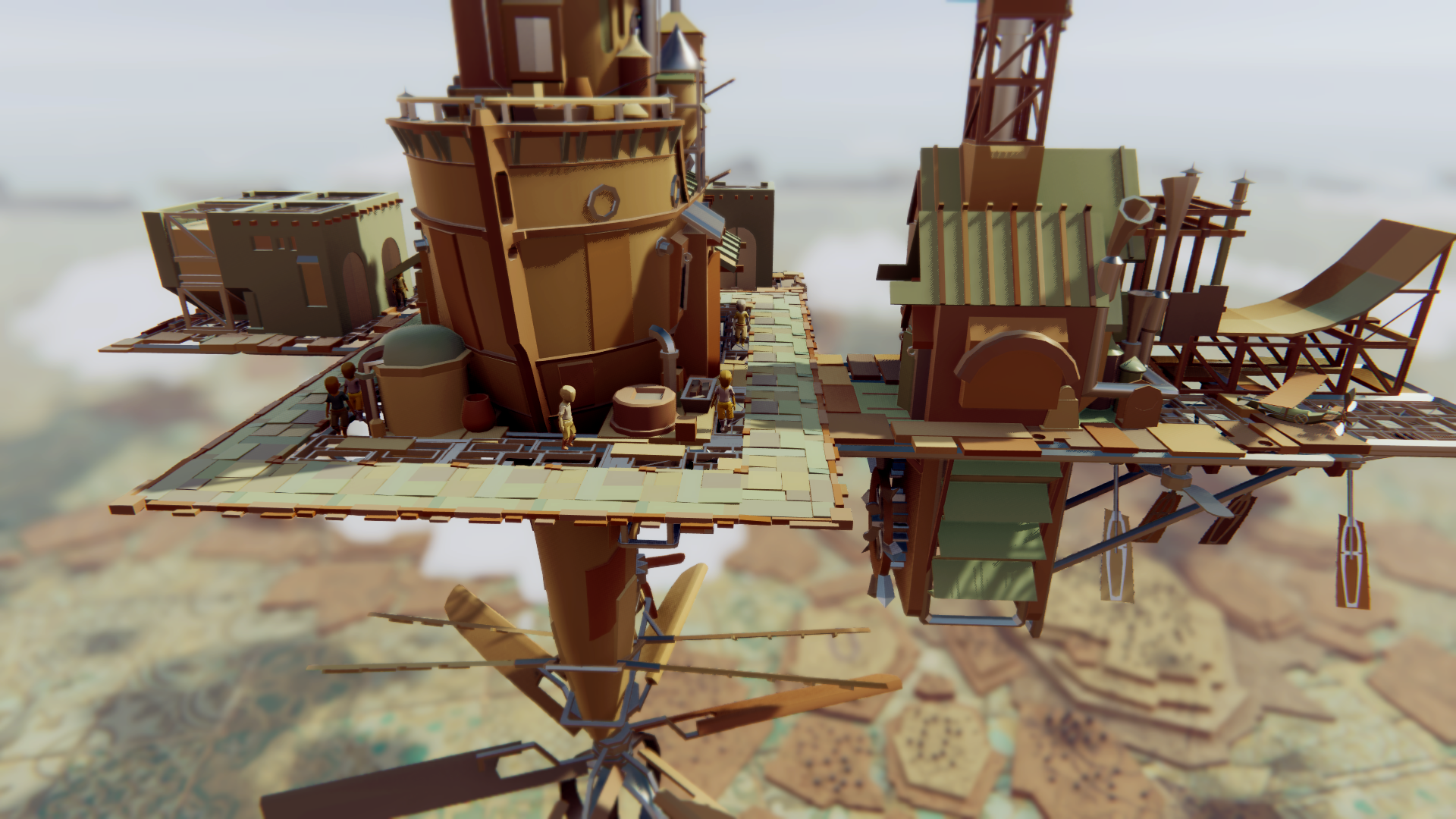

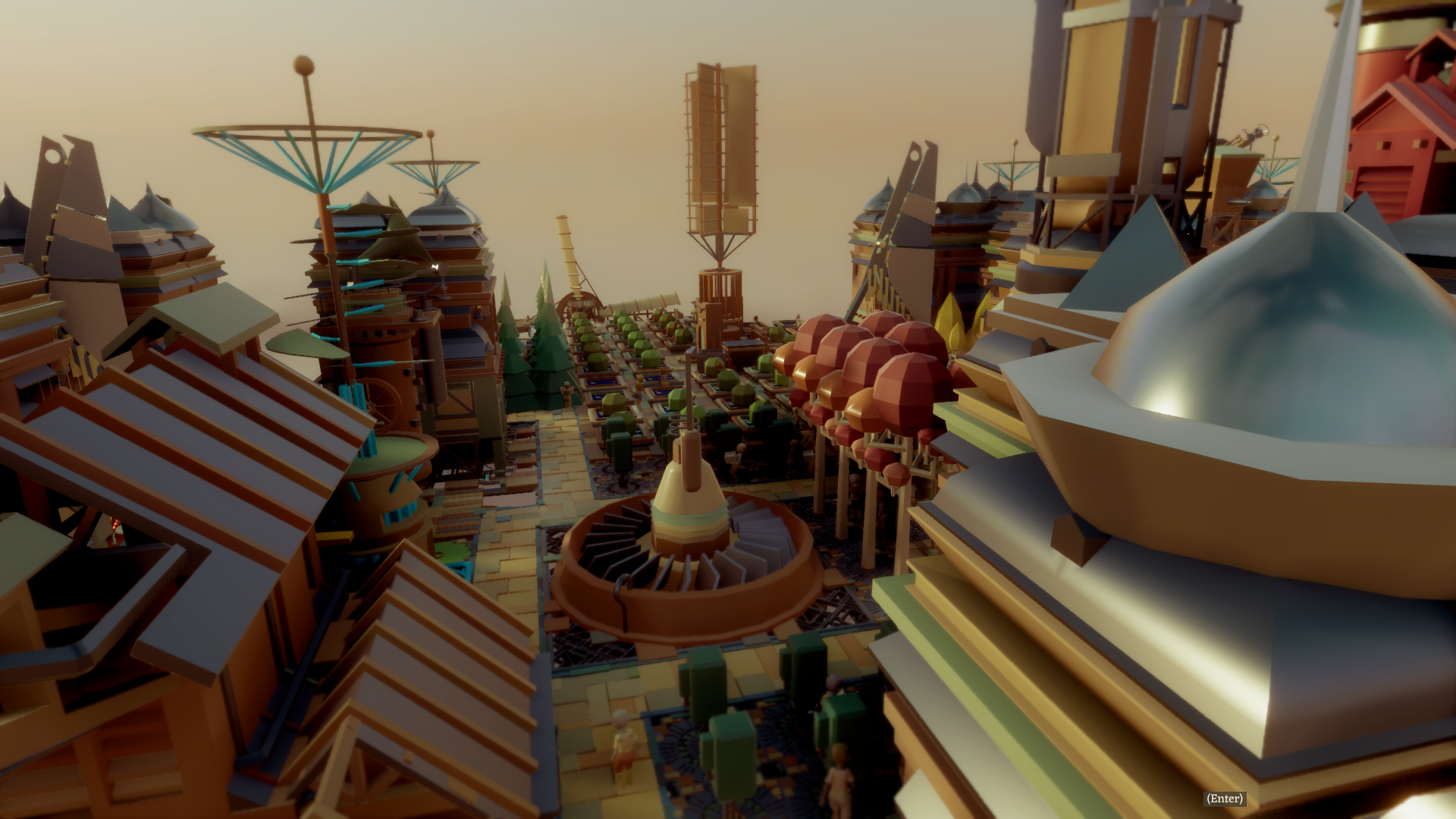

Occasionally, during its grazing, the Kingdom uncovers a town, a tiny toe-nail clipping of huts and cooking fires, poking from the dusty mosaic tiles and cracked flagstones of the map. It sends emissaries to gather up the people of the earth and transform them into creatures of the air. Some surface-dwellers are easily won over by tales over high adventure. Others are resistant, put off by hints of dissatisfaction in the streets above. No matter. The Kingdom will be back for them, once its existing residents are happier. A little less often, the Kingdom comes across another kingdom - a towering sandstone palace or a jaunty stack of windmills, its name embossed on the ground nearby. When it encounters such places it descends in greater earnest, blotting out the sun and filling the ears of the locals with its Prophecy - the legend of the Airborne Kingdom as unifier of humanity, stepping stone to heaven. While not always receptive to these promises of a golden tomorrow, the surface kingdoms are willing to pledge loyalty in return for a couple of favours, typically of the “fetch this” and “supply X of Y” variety. One asks the Airborne Kingdom to track down a special breed of tree to repopulate a sacred grove. Another asks it to carry three scholars to neighbouring cities. Others simply need wood and cloth to build new homes. The Kingdom carries out all these requests graciously - it very frequently arrives with the necessary materials already in hand - but it has demands of its own. Technologies to research for new building types, traded for relics obtained from ruins around the land. A formal alliance consummated by an hourly tribute of wood, iron or cloth, transported by air (the other kingdoms have no planes to begin with, but the Airborne Kingdom is only too happy to build them a skyport). And above all, people - people to spin the Kingdom’s sails and shovel coal into the engines, people to staff the kilns and smelters, haul goods to its warehouses and tend its vertiginous farms. For every fresh shipment of bodies the Kingdom must expand, wrapping clip-on paths and stackable dwellings around itself like another layer of treebark. At longer intervals, it adds new rotors, wings, propellers and fans to keep its increasingly misshapen bulk aloft. Once it has allied with every nation on earth and hoovered up enough people, the Airborne Kingdom will form a Great Council and bring about the Prophecy’s completion. What it will do then is, as the saying goes, a story for another day. As the above hopefully suggests, it’s easy to imagine a much nastier version of Airborne Kingdom than the game you get. What you get is a handsome, engrossing eight-hour city-building sim whose big trick, as in the Homeworld series, is that your base of operations is also your means of travel. It’s a pretty and intricate, game-length urban puzzle founded on a core of simple resourcing missions, with art direction that blends Disney Orientalism with Studio Ghibli. There is absolutely no darkness to it, no whisper of a misgiving about the premise of a mobile theocracy rinsing the geography in passing, and frankly, this feels like a wasted opportunity. It’s also not as exotic as it may look in screenshots. The Airborne Kingdom differs from its ground-dwelling neighbours in that you’ll need to keep hunting for coal to keep flying. You’ll also need to balance your city by spacing out its various flight mechanisms, or else face a city-wide drop in morale - it’s harder to keep the faith, after all, when you’re eating and sleeping at right angles. The fundamentals, however, are bread-and-butter stuff. Food and water are the bare necessities; beyond that, you need wood, iron, clay, cloth and glass for construction. You need hangars to forage for all of the above, and paths to glue your structures together. You need academies to research buildings and upgrades, and warehouses for storage. Last but not least, you need culture buildings to motivate your citizens and recruit newcomers to your cause. The world below all this is split into three biomes with four kingdoms apiece and mildly different terrain conditions. You’re given some idea of what to expect as you cross the border, allowing you to halt, rebuild and stockpile if necessary. The mountains up north are packed with mineral ores but light on food and water. The inland archipelago to the east abounds with cotton trees for cloth-making, but coal is scarce. Each surface kingdom also has different technologies to share: the order in which you visit them, together with the factors at work in each biome, shapes the city that swells around the glorified airship you start off with. There isn’t really an optimal path through the environment - quests sometimes require that you produce a particular resource, but the raw materials together with the requisite technologies are always found nearby. This is just as well, because it can take many moments to travel between hotspots, and while the setting can be mesmerising, it is functionally just a collection of quest waypoints and things to gather. As your Kingdom’s headcount increases, your citizens grow more picky. Far from being contented with full bellies and adequate living space, they’ll ask that you bolt the cultural hallmarks and luxuries of the cities you visit into your urban design. Temples and shrines supply opiate for the masses, clinics keep people healthy, and streetlights ensure that everybody feels safe at night. These social variables are distilled (a little too straightforwardly, perhaps) into a Happiness indicator, ranging from Angry to Jubilant. The happier people are, the more you’ll be able to recruit from the settlements below. The unhappier they are, they more likely they are to up sticks, perhaps sabotaging your operations at a critical juncture. Meeting these rising expectations, together with the fairly mechanical-feeling kingdom quests, gives Airborne Kingdom a basic tempo of exploration and consolidation - but you can always research and build things on the move. Helpfully, the camera locks to your city when you open the construction menu, and building templates snap together gratifyingly if there’s space and material for their construction. Placing structures gets fiddly as the Kingdom grows, but working out how to fit everything together without scuttling the whole is the game’s greatest joy. At its most endearing, there’s the same, playful yet pensive sandbox vibe you find in a “casual” city sim like Islanders or Townscaper. Providing you balance your creation and have enough lift, you can push and pull the Kingdom into any shape you choose - a triangular steampunk behemoth with an observatory on each wingtip, a street as long as the horizon, a fairytale citadel with the shortest buildings tucked around the rim. Beyond the problem of balance, the key constraint is grouping buildings by type - people don’t like living near noisy engines or workshops, and production-boosting buildings such as water filters need to be within range of the structures they amplify. These pressures might limit your architectural ambitions, but it’s fun nonetheless to let your city flourish under its own direction. I favoured expediency during my playthrough, and by the end of the game, I’d cobbled together a wonderfully incoherent but plausible-feeling labyrinth of gardens, temples, furnaces and rotor blades, carried along by not-quite symmetrical wings and fans, paths scurrying all over as though plotted out by ricocheting bullets. There’s a resource penalty for shifting buildings around but it’s modest, which means you can meddle with the Kingdom as the occasion demands, though it’s best to do so while pausing time to avoid upsetting the citizenry. The more you engross yourself in details like these, the less you’ll notice Airborne Kingdom’s rather forced air of optimism, the way it skirts round the darker implications of its narrative. There’s no military element, and you’re always persuading people to join your cause rather than threatening them. But it’s hard to look at your Kingdom, looming over some hamlet like a Star Destroyer, and not feel that there’s a touch of old-fashioned physical coercion at play. Likewise, it’s hard to see the business of receiving tribute from allies as anything but a sanitised version of exacting spoils from the defeated. I offer this in part because it feels dishonest - the game literally describes your Kingdom as an empire, and empires shouldn’t be cast as saviours. But before you call me out for being just another moralising critic, I also think Airborne Kingdom would be a much more interesting game if it was alive to the violence implied by the spectacle of a massive flying city with its own airforce, roaming a setting that has no agency of its own. The Airborne Kingdom wants to be Laputa, Studio Ghibli’s Castle in the Sky, but there’s more than a whiff here of the urban predators of Philip Reeve’s Mortal Engines. Another way of thinking about Airborne Kingdom is that it is a curious inversion of 11-Bit’s Frostpunk, the same concepts branching off in different directions. In Frostpunk, coal pins your settlement to the earth with a great, smoking spire. In Airborne Kingdom, coal gives it the power to explore. In Frostpunk, you create room for expansion by burning coal for heat. In Airborne Kingdom, you create room for expansion by burning coal for height. Both games are about highly centralised city-planning, and both games are post-apocalyptic, though Airborne Kingdom’s sunny expanse of plateaus, pools and clouds (which shrink back from your cursor, as though from the gaze of a god) is a lot more inviting than Frostpunk’s wintry wasteland. Where they differ is in their sense of the human cost of all that building and expansion. In Frostpunk, people lose limbs to frostbite and children are put to work in the furnaces. You pass draconian laws and weather the inevitably horrible results. In Airborne Kingdom, the greatest existential threat you face is people throwing tantrums about the shortage of teahouses. Both are escapist fantasies, but one is lent power by its willingness to investigate grim prospects the other refuses to entertain. The Kingdom might sell itself as a unifier, binding scattered nations into an empire, but the more you play, the more you sense that it wants to leave the earth behind. This is as much about the story you’re told as the one implied by the research and construction tree, which sees you inching closer and closer to self-sufficiency. Later in the game, fully upgraded water condensers and farms make foraging something you do occasionally to plug a hole, rather than incessantly. Charcoal for your engines can be produced from wood supplied invisibly by allied kingdoms. The planes issue from your hangars less and less, and you pay more and more attention to cosmetic elements, repainting the Kingdom’s domes in ghastly pinks and purples, and filling the gaps in the floorplan with shrubberies and streetlights. When I started playing I was fascinated by the landscape beneath. I wanted to hear more about the abandoned, crumbling temples and foundries, the different forms of government and social relations you’re told about when you visit each city. I craved an extended mission or two to dig into the origins of the Prophecy. I wondered about the possibility of an antagonist. But towards the end, I felt only indifference, which is a more rarefied, civilised kind of cruelty than the urge to pillage. It feels like this game drifts in the shadow of another game in which the Airborne Kingdom is exactly what it looks like: a ponderous, uncaring monster that eats the world in order to set itself free.